Talking Design With Princess Christina of Sweden

Where Ordinary Is Beautiful, and Vice Versa

04/29/99

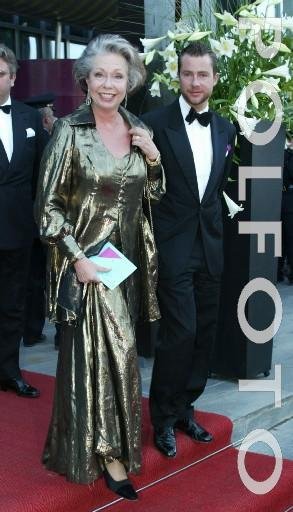

EARLIER this month, Christina Magnuson, a sophisticated 50-something Swede, sat in a Manhattan hotel suite and discussed well-designed juice glasses, toothbrushes, kitchen utensils, furniture, cars and houses.

"Design is one of society's largest cultural assets," she said, a gauge with which to measure the aspirations of a civilization.

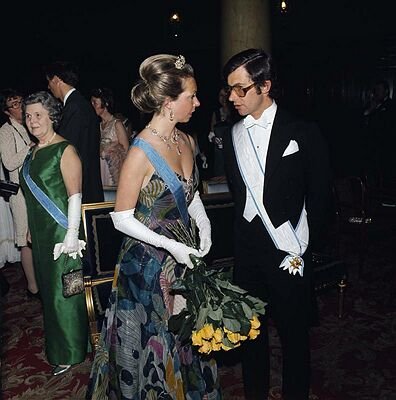

The fact that Mrs. Magnuson is a sister of King Carl XVI Gustaf and thus a princess, and that she lives with her husband and three children in a large villa on the grounds of Ulriksdal Palace in Stockholm, might make her interest in juice glasses seem strange. But in Sweden, where the creation of everyday objects has been elevated to a fine art, the term "Design Princess" is a serious honorific.

The Princess, whose primary career is as chairwoman of the Swedish Red Cross and whose royal status in a socially democratic country makes her something of an anomaly, has spent the last 10 years promoting design in the hopes of establishing a museum in Stockholm. For now, there is a temporary exhibition space called the Forum for Form — which she and Swedish designers, critics and curators refer to as a "museum in embryo."

Outsiders are usually surprised that Sweden has no national design museum, given the country's reputation. But this says a lot about Sweden.

"Because we're used to the lines and style of Swedish design, we tend to think of the things that surround us as very ordinary," the Princess explained.

"When we get outside attention, we start to take notice of how special it really is."

There has been no dearth of outside attention. Wallpaper magazine recently dedicated an entire issue to the current Swedish design scene. The International Contemporary Furniture Fair, to be held in New York next month, will feature a number of young Swedish stars like Thomas Sandell and Bjorn Dahlstrom at the Totem design booth. And there are a host of new wave Swedish companies like David Design, Asplund, Box Mobler and CBI.

Since the 1940's, most Swedes have lived with textiles, glass, ceramics, furniture and flatware that seamlessly merge craft and industry. Such design seems to be a natural extension of the country's social ideals. Recently there has been an international revival of interest in early-20th-century Swedish companies like Svenskt Tenn (the name means Swedish Pewter), the decorative arts workshop that brought Swedish design to the 1939 New York World's Fair. Some of Svenskt Tenn's exquisite metal jewelry (by its founder, Estrid Ericson) is being reproduced at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and nine of its wildly vibrant textiles (by the Austrian transplant Josef Frank) are still available from Brunschwig & Fils.

Neighboring Danes and Finns in the 1950's and 60's may have been equally responsible for the widespread popularity of curvilinear chairs, surfboard tables, biomorphic glassware and striking geometric rugs. But it was a 1955 exposition in Helsingborg, Sweden, that spread Scandinavian design abroad.

In fact, a new design store in Manhattan is called H55 in honor of the exposition. The store's chunky, brightly colored 50's glass vessels by Sven Palmqvist speak volumes about the enthusiasm and expectations of that time in Sweden, which had just experienced a 50-year climb from poverty to prosperity. The decorative ceramics of Henrik Allert and Stig Lindberg show the era's blending of fine and applied arts.

It was a celebration of this heritage that brought Princess Christina to New York, where she opened a seminar on 20th-century Swedish design sponsored in part by the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts.

The Princess imbibed Swedish creativity from the priceless handcrafted artifacts and artwork that filled her childhood home, the Royal Palace in Stockholm, and the functionalist design of her youth in the 50's and 60's. Her grandfather King Gustaf VI Adolf often discussed his interest in Chinese porcelain. She studied art history at the University of Stockholm and attended Radcliffe College for a year in which she formed her passion for Warhol and Rauschenberg. Moreover, Sigvard Bernadotte, her uncle, is Sweden's first modern industrial designer. Count Bernadotte, now 92, created everything from silverware to plastic bowls.

"At a certain point I started feeling that objects spoke a language," she said.

By lineage, the Princess, who is married to a businessman, Tord Magnuson, is actually more French and German than anything.

"If there's an ounce of Swedish blood in me," she said,

"it must be diluted 100 times. Yet I'm terribly Swedish."

She appreciates glass above any other decorative art.

"Glass is one of the joys of life," she said.

"It's an integral part of the Swedish experience — to drink out of it, to have it in the window with the light shining through, to fill it with flowers or leaves." So it's not surprising that she keeps an extensive personal collection of Swedish glass.

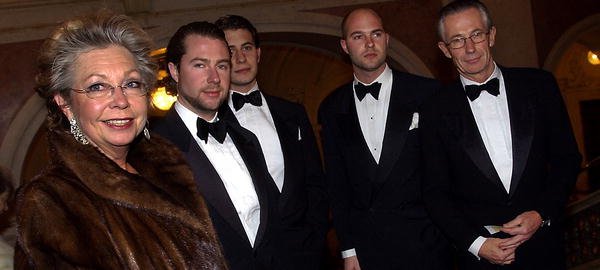

In New York, Princess Christina was notably self-effacing and retained her cool during a photography session, when a wall of ice, built as a backdrop, collapsed.

During her stay she inaugurated a new collection of Skruf glassware by Ingegerd Raman at the American Craft Museum, where an exhibition of turn-of-the-century Swedish Rorstrand porcelain runs through May 23. Rorstrand's playful Art Nouveau vases with cavorting sea creatures present one extreme of 20th-century Swedish design. Ms. Raman represents the other side: in their severe Nordic simplicity, her ice-clear glass carafes and decanters are as austere as Lutheran churches.

Both strands will be represented at a new exhibition, called H99, in Helsingborg, to begin in July. With mid-century so close in history's rearview mirror and the turn of the century just around the corner, the show will feature Swedish design and architecture from the 1950's to the infinitely adventurous present.

FROM NEW YORK TIMES, 04/29/99, BY ANDREA CODRINGTON.