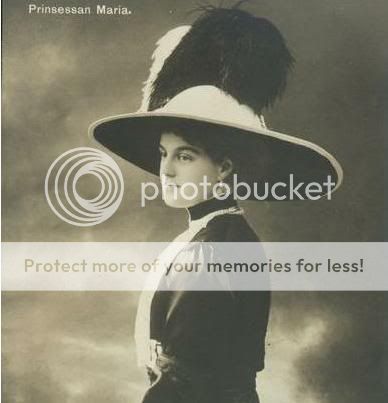

Perhaps it was because she had never had much of a childhood herself that Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna of Russia, daughter of Grand Duke Paul Aleksandrovich and Aleksandra of Greece, had no great affinity for the toddlers of this world. She knew this all too well. All the hurtful ways adults had of dealing with her in her own infancy, she wrote, were strangely to shape all her relations with children - even with her own.

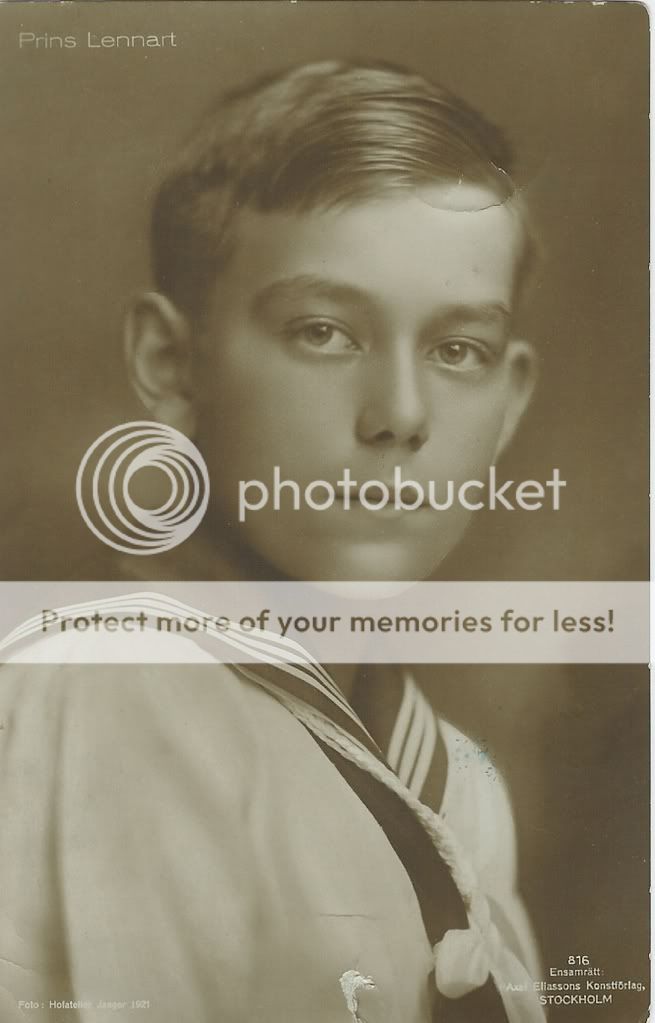

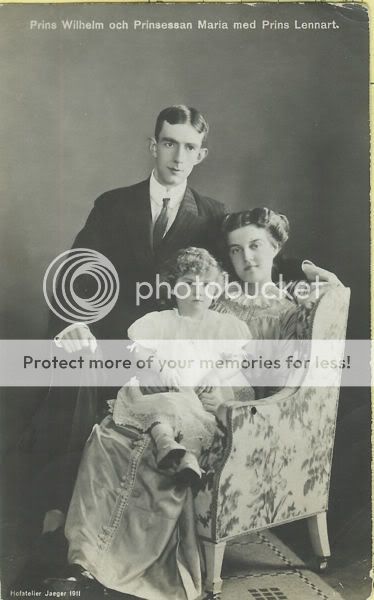

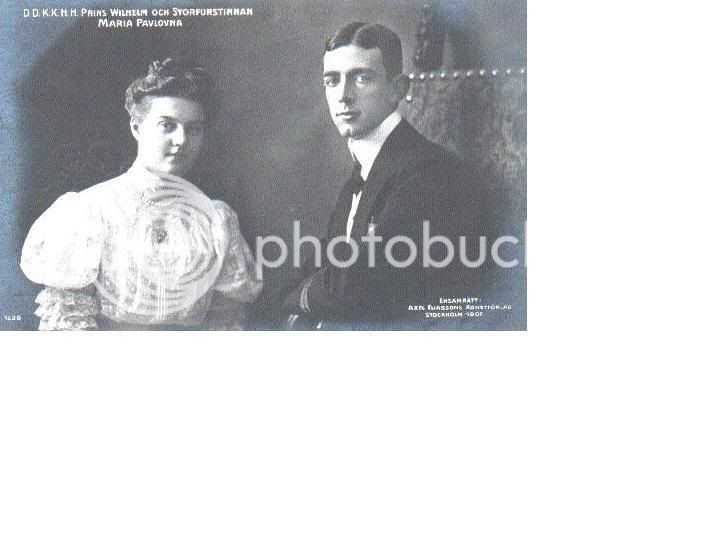

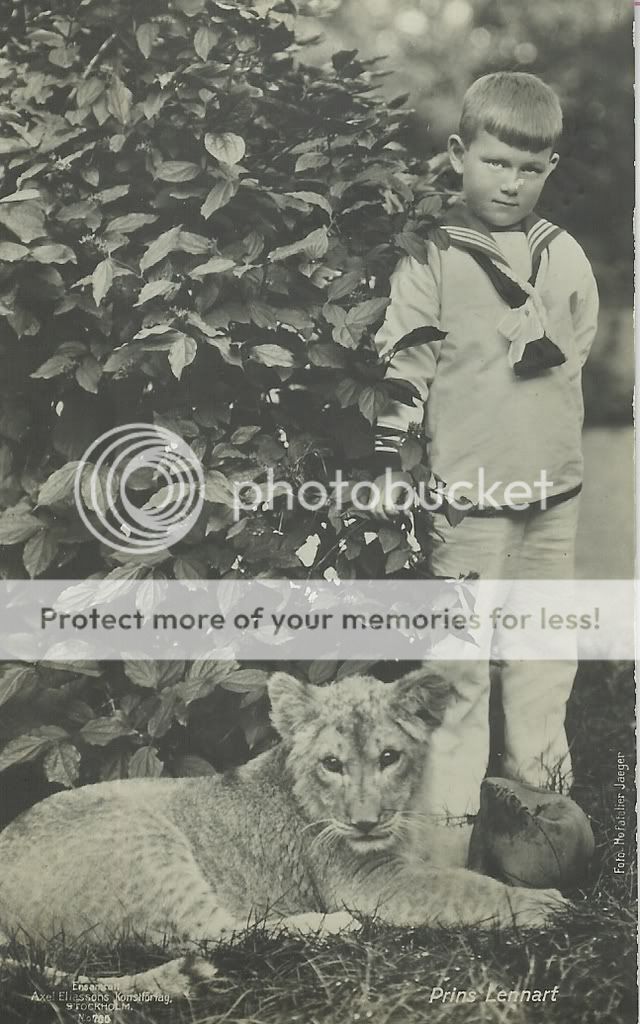

Certainly, in later years, on coming to know her son by Prince Vilhelm of Sweden, Count Lennart Bernadotte af Wisborg, Marie obliged the tall young man to address her by her given name rather than 'mother', a requirement that seems not to have sat comfortably with either the boy or the man. If this appears strange, it is well to remember that Marie's mother, after all, had died tragically young, following the birth of a son, Grand Duke Dimitri, when Marie was less than two years old; and not long after, her father took up with a beautiful lady whose commoner origins eventually got both sent into Parisian exile. Marie and Dimitri, traumatized, were taken into the bosom of their father's family, the Romanovs, whose childrearing techniques, generally speaking, had not the best of track records, and specifically into the bosom of a marriage that could hardly be called the best example for adults, let alone bewildered children.

On this unpromising anvil Marie forged a character that was nothing if not self-reliant. But her lifelong inability to relate to children was to prove that however lucky she was to have found a lifeboat, come the sinking of the Titanic of Russia's ruling caste after 1918, the few treasures she saved from the wreckage were wanting when compared to those she had long ago left behind. Luckily for Marie, her own child had no intention of doing the same.

'Born in 1890', Marie writes in her first volume of memoirs, The Education of a Princess, 'I have stepped through the ages." Her earliest memories were of lazy country estates populated by armies of servants, fortresses haunted by reverberations of past strife and bloodshed, of palaces that were such confections of gold, silver, and marble that they outdistanced the fairy tale fastnesses described by the most fantastical nyanyas. As she wrote of these things, looking out on Depression-era New York's traffic-clogged streets and towering buildings, Marie must indeed have wondered which was real and which make-believe.

In the Russia of 1890 (as in the Russia of a century later), life would remain mediaeval in certain respects for the many and up-to-date for a relative few. Marie belonged to the second category in so far as she grew up with conveniences'electric light, telephones, automobiles'that remained mysterious if not terrifying to the majority of her cousin Tsar Nicholas II's subjects. But where the Romanov family regulations were concerned, mediaevalism enjoyed a biblical life-span. The Fundamental Laws, scripted by Tsar Paul I, threw the book at all sorts of troubles which he wished never to see repeated. Women, for example, were to be barred from ruling'one didn't want another Catherine the Great roving unchecked upon the face of Holy Russia. For added difficulty, spouses taken by all members of the ruling family were to be equal-born. By the end of the 19th century, this requirement had set up a towering standard of best behavior, directed mainly toward the males of the family, which many of them opted to sidestep by taking morganatic wives. What a Grand Duke gained in domestic bliss, he and his children by such a woman lost in giving up all rights to the Russian throne or the family name.

This risk Marie's father, Grand Duke Paul Aleksandrovich, proved himself willing to run. His first wife had fallen ill shortly after arriving for a visit to Ilinskoie, the unpretentious country estate of her brother-in-law Grand Duke Serge Aleksandrovich outside Moscow, in September 1891. Six days in a coma, Aleksandra was delivered of a premature son, Grand Duke Dmitri, and then died. No one could believe that the lovely Grand Duchess Paul, only 21 years old, was no more, least of all her adoring husband. At the funeral in Peter and Paul Cathedral, Paul couldn't bear to have the coffin closed, and Serge had to take him in his arms and lead him away.

Of the many failings that can be ascribed to those Romanov princes who married or mistressed in defiance of the Fundamental Laws, coldness of heart was rarely among them. When four years into his widowerhood Grand Duke Paul met Mme Eric von Pistolkors, an elegant Petersburg socialite of noble Hungarian ancestry, he and the future Princess Paley literally fell in love at first sight. A natural son, Vladimir, brought about Olga von Pistolkors' divorce from her Cheval Garde officer husband in 1897; and in autumn 1902, the Grand Duke was married to his lady, in Livorno, Italy, by an Orthodox priest ignorant of their identities. Unable to return to Russia, the couple took up residence in a mansarded villa in Paris, No. 2 Avenue Victor Hugo, where it seemed they were to dwell happily ever after.

Having been informed by mail of their father's marriage, and devastated by the news, the 12 year old Marie and her 11 year old brother were placed in the care of their uncle, Grand Duke Serge, and his wife, the coldly beautiful Princess Elisabeth (Ella) of Hessen, sister of Empress Aleksandra. Marie claimed her childhood ended in this year of 1902, but she describes in her memoirs even before that a girl not so much infant as miniature adult. Some instinct warned her early on that the way of life led by her family was off kilter compared to the rest of the world, and was not to last. Indeed, close to this time she pictures herself, sitting on the floor of the nursery, attempting to button her own boots. In the event of a revolution, a modern princess had to know how to look after herself.

This Marie was to do very well even before revolutions began to rain down. She lived with an aunt who when not ignoring her entirely seems to have been as chilly as her sister was overwrought. Once Marie found Ella wearing court dress, her swan-like neck emblazoned with sapphires, and impulsively kissed the pale flesh under the gorgeous stones. Ella's response was to stare coldly, stinging her niece to the heart.